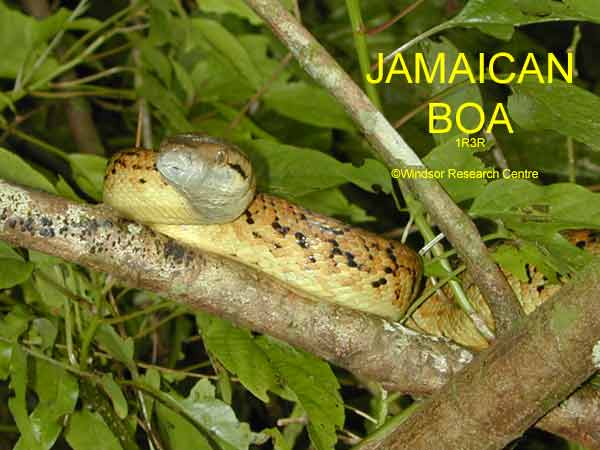

The Jamaican (Yellow) Boa is endemic to Jamaica - it occurs nowhere else in the world. It is the island's largest native terrestrial predator and, as with all species in the Boidae family, it kills its prey by constriction.

What are we really saying? The Jamaican Boa is NOT venomous!

Indeed, none of Jamaica's 7 extant species of snakes is venomous. Not only is the boa not a threat to humans, it's actually extraordinarily beneficial. Rats are a major component of the boa's diet in forest edge and farm habitat, so when a farmer finds one coiled in a coffee tree or banana plant, it's digesting a meal which would have otherwise damaged his or her crops.

If you are lucky enough to have a wild boa take up temporary residence in your house, as we are periodically, you will find that your rat problem magically goes away.

Unfortunately, most Jamaicans are not as thrilled with the idea of having a wild boa living in their house. The traditional Jamaican antipathy to reptiles (in general) and snakes (in particular) is a serious problem for their conservation. In the absence of an education programme, snakes are killed on sight. And when we say "killed," we mean but good: chop it with a machete, drive over it with a truck and then back-up to squash it a second time, pour rum over it and set it ablaze. This intense persecution of such a benign and beneficial animal, coupled with continuing habitat loss and fragmentation of remnant forest patches, is a serious threat to Jamaican Boa populations.

During her research on the breeding biology of Black-billed Parrots, Susan identified that boas were a major cause of nest failure (Koenig 2001) . . . or to look at the other side of the coin: parrots are a food resource for boas when nests are accessible (Koenig, Wunderle & Enkerlin-Hoeflich 2007).

But remember the third paragraph above: rats are the major component of the boas' diet so we need not worry about the birds -- Nature is in balance in the interior of Cockpit Country and we respect all components of the web of life. Local farmers, however, were not so keen and immediately offered to continue killing all boas. Indeed, Susan and her crew periodically encountered chopped boa carcasses in the forest. We realized people were killing snakes for a number of reasons, including a mis-informed fear that boas were venomous, the Bible told them snakes were evil, and they had no knowledge that boas could be beneficial to their farm crops. So we began an informal education campaign, where if someone finds a boa they could come and tell us and we will capture the animal. This gives us the opportunity to show people that boas are gentle when they are handled safely and respectfully (NOTE: remember, don't catch them unless you have a permit and have been shown how to properly hold a snake -- you can hurt them, esp. their jaws, if you don't know what you are doing!) We often ask the "obnoxious young man" at the back of the crowd to help us hold the snake -- sexism is great, if Susan can touch a snake, the young man has to defend his manhood! We spend a lot of time talking about the benefits of boas. As Miss Herma says, "She never love de suh-nake like Miss Susan, but she keep her cutlass down now when she see one: him no trouble her."

Wild Life Protection Act (1945). Endangered Species (Protection, Conservation and Regulation of Trade) Act (2000) The boa also is protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES): it is on Appendix I, the most-restrictive listing for trade. |

Windsor and, more generally, Cockpit Country, is one of the few remaining strongholds for this vulnerable snake, and we are certainly pleased with our community's change in attitude from the previous decade. Indeed, we've had more than 100 encounters with boas since we started our education-outreach in Windsor - - that's a lot of boas that were NOT chopped by people!

After we catch a snake, we return to WRC to collect data on sex, weight, and length of each animal. Although each boa has a unique colouration and marking pattern, this can change slightly over time and doesn't allow us to identify individuals if we encounter them in the future. So, we also implant under the skin a small, uniquely-numbered microchip (a Passive Implantable Transponder (PIT), manufactured by TROVAN). If the boa isn't gravid (pregnant) we'll keep it in a terrarium for up-to two weeks to collect any feces which it passes - this allows us to get a better understanding of their diet. We then return it as close as possible to its point-of-capture (its home territory).

PIT tags enable us to get a better understanding of site fidelity and the lifespan of wild Jamaican Boas. Whenever a tagged boa is recaptured, we can go back to the data of the 1st capture and learn how much it has grown, how far its moved around, and of course, how many months or years have passed. So far, the longevity record goes to a female (PIT 00-068B-5E86):

- 1st capture (T1) = 18th December 2006; SVL = 142 cm; Weight = 1.75 kg

- 2nd capture (T2) = 14th June 2010; SVL = 152 cm; Weight = 2.55 kg

- 3rd capture (T3) = 8th December 2013; SVL = 174 cm; Weight = 3.20 kg

|

Fortunately, in 2008, Dr. Craig Rudolph was on-holiday in Jamaica, enjoying our endemic birds in Cockpit Country, and enjoying a "Sugarbelly Dinner" . . . and the next thing we knew, we were able to properly study the movements and activity patterns of Jamaican Boas thanks to funding support and / or the loan of equipment from USDA-Forest Service, USFWS Wildlife Without Borders, Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, and Windsor Research Centre. The photo shows Craig (on the left) giving guidance to Dr. Michael Whittingham DVM as he prepares to surgically implant a radio transmitter. We are enormously grateful to "Dr. Mike" for looking after all of the boas.

From 2008 through 2012, we radio-tracked Jamaican Boas in-and-around Windsor. You can learn more about boas moving around in their natural home ranges (click here) or watch Elvis (aka 00-068B-78D7) as he shimmies up a tree at night.

Photo on left: the Boa clearly has no problem climbing even this smooth-trunked tree. She'll "hitch" her way up the tree.

Is it nice to move a boa?In one case we moved a boa about 500 m from a limestone quarry on the coast: Mike intervened in time to stop her being killed and we thought we would be "nice" and move her out of harm's way. We also had a very good dialogue with the quarrymen!

Of course, the boa didn't think what we did was very "nice" -- moving her out of her home yard without so much as "by your leave." A week later, the quarry phoned us to say they found another boa:

Yippee! Measure of Success!! They didn't kill a snake!!!

But we were all rather surprised that it was the same boa we had moved the previous week. We immediately reviewed the published literature, realized not a single herpetologist would be surprised that she found her way "home", and realized that we (and NEPA and EIA consultants and everyone else on Jamaica) needed to get some proper data on how translocation affects boas. Examining this question was also part of our radio-tracking research....stay tuned for the webpage-under-construction!

Reynolds et al. (2013) recommend that West Indian boids be restored to the genus Chilabothrus and Epicrates be retained on the mainland. Although the IUCN RedList recognizes the change in nomenclature, national legislation (e.g., Wild Life Protection Act, 1945) and international conventions (e.g. CITES - 5th February 2015) retain usage of Epicrates for the Jamaican Boa. To avoid confusion, particularly as it relates to law enforcement on Jamaica, we retain usage of Epicrates until the WLPA and CITES Appendix is amended.

SELECTED LITERATURE ON THE JAMAICAN BOA:

Barbour, T. 1910. Notes on the herpetology of Jamaica. Jamaica Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 52:272-301.

Bloxam, Q.M.C. 1977. Maintenance and breeding of the Jamaican boa Epicrates subflavus at the Jersey Zoological Park. Dodo, Journal of the Jersey of Wildlife Preservation Trust 14:69-73.

Bloxam, Q.M.C., and S. Tonge. 1981. A comparison of reproduction in three species of Epicrates maintained at the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust. Dodo, Journal of the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust 18:64-74.

Cruz, A., and S. Gruber. 1981. The distribution, ecology and breeding biology of Jamaican amazon parrots. Pp. 103-132In Conservation of New World Parrots. R. F. Pasquier (Ed.). Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

Dávalos, L.M., and R. Eriksson. 2004. Chilabothrus subflavus (Jamaican boa) foraging behavior. Herpetological Review 35:66.

Diesel, R. 1992. Snakes of the Cockpit Country. Jamaica Naturalist 2:29-30.

Gosse, P.H. 1847. The Birds of Jamaica. John Van Voorst, London, UK.

Gosse, P.H. 1851. A Naturalist’s Sojourn in Jamaica. Brown, Green and Longmans Press, London, England, UK.

Gibson, R. 1996. The distribution and status of the Jamaican boa Epicrates subflavus (Stejneger, 1901). Dodo, Journal of the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust 32:143-155.

Grant, C. 1940. The herpetology of Jamaica, II. The reptiles. Bulletin of the Institute of Jamaica Science Series 1:61-148, 3 plates.

Koenig, S. E. 2001. The breeding biology of Black-billed Parrot Amazona agilis and Yellow-billed Parrot A. collaria in Cockpit Country, Jamaica. Bird Conserv. Int. 11: 205-225.

Koenig, S.E. and M. Schwartz. 2003. Epicrates subflavus (Yellow boa) diet. Herpetological Review 34:374-375.

Koenig, S.E., J.M. Wunderle, Jr., and E.C. Enkerlin-Hoeflich. 2007. Vines and canopy contact: a route for snake predation on parrot nests. Bird Conserv. Int. 17:79-91.

Lynn, W.G., and C. Grant. 1940. The herpetology of Jamaica. Bulletin of the Institute of Jamaica, Science Series1:1-148 pp.

National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA). 2007. A Recovery Action Plan for the Jamaican Boa (Epicrates subflavus): A look at the conservation needs of Jamaica’s largest native terrestrial predator. Prepared by the Biodiversity Branch of NEPA, January 2007. Kingston, Jamaica.

Oliver, W.L.R. 1982. The coney and the yellow snake: the distribution and status of the Jamaican Hutia Geocapromys brownii and the Jamaican boa Epicrates subflavus. Dodo, Journal of the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust 19:6-33.

Oliver, W.L.R. 1986. Nanka or yellow snake: a Jamaican boa. Jamaica Journal 19: 2-7.

Prior, K. A., and R.C. Gibson. 1997. Observations on the foraging behavior of the Jamaican boa Epicrates subflavus. Herpetological Review 28:72-73.

Reynolds, R.G., M.L. Niemiller, S.B. Hedges, A. Dornburg, A.R. Puente-Rolon, and L.J. Revell. 2013. Molecular phylogeny and historical biogeography of West Indian boid snakes (Chilabothrus). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 68:461-470.

Schwartz, A. and Henderson, R.W. 1985. A guide to the identification of the amphibians and reptiles of the West Indies exclusive of Hispaniola. Milwaukee Public Mus., 165 pp.

Schwartz, A. and R.W. Henderson. 1991. Amphibians and Reptiles of the West Indies: Descriptions, Distributions, and Natural History. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, Florida.

Sloane, H. 1725. A voyage to the islands Madera, Barbadoes, Nieves, St. Christophers, and Jamaica; with the natural history of the herbs and trees, four-footed beasts, fishes, birds, insects, reptiles, &c. of the last of those islands, vol. 2. London.

Stejneger, L. 1901. A new systematic name for the yellow boa of Jamaica. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 23:469-470.

Stewart, J. 1823. A View of the Past and Present State of the Island of Jamaica with remarks of the moral and physical condition of the slaves and on the abolition of slavery in the colonies. Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale-House and G. & W. B. Whittaker, London, UK.

Tolson, P.J. 1987. Phylogenetics of the boid snake genus Epicrates and Caribbean vicariance theory. Occ. Pap. Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan 715:1-68.

Tolson, P.J. and R.W. Henderson. 1993. The natural history of West Indian boas. R&A Publishing, Middlesex, England.

Tzika, A., S.E. Koenig, R. Miller, G. Garcia, C. Remy, and M. Milinkovitch. 2008. Population structure of an endemic vulnerable species, the Jamaican boa (Epicrates subflavus). Molecular Ecology 17:533-544.

Tzika, A. and M.C. Milinkovitch. 2006. Conservation genetics of the Jamaican Yellow Boa (Epicrates subflavus). Report of field-trip to Jamaica.

Vareschi, E. and W. Janetzky. 1998. Bat predation by the yellow snake, or Jamaican Boa Epicrates subflavus. Jamaica Naturalist 5:34-36.

Vernon, B.J. 1848. Early Recollections of Jamaica, with the particulars of an eventful passage home via New York and Halifax, at the commencement of the American War in 1812; to which are added, trifles from St. Helena relating to Napoleon and his suite. Whittaker and Co., London, UK.

Wilson, B.S., S.E. Koenig, V.R. Van, E. Miersma, and D.C. Rudolph. 2011. Cane toads a threat to West Indian wildlife: mortality of Jamaican boas attributable to toad ingestion. Biological Invasions 13:55-60.